What is a table?

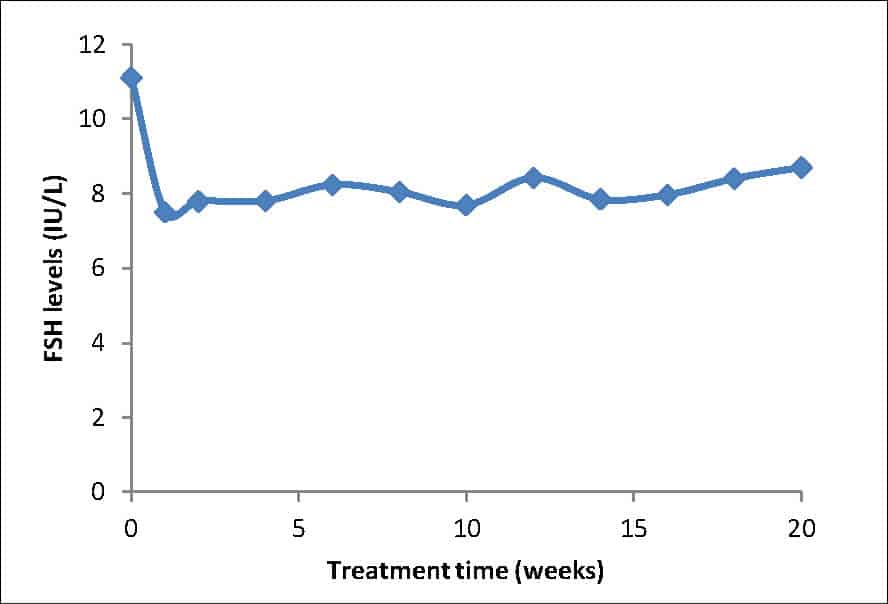

Tables present the results of data or information collected from a study. The purpose of a table is to present data summaries to help the reader to understand what was found. Not all data needs to go into a table: some results are simply presented as written text in the results section; data that shows a trend or a pattern in between variables is presented in figures, while additional data not necessary to explain the study should go into the appendix.

Tables should convey data or information clearly and concisely and allow the key message to be interpreted at a glance. Tables often include detailed data in rows and columns, while sub-columns are often nested within larger columns.

Designing your table

Once you have decided what data to present, jot down a rough draft of the table headings on paper to determine how many columns and rows you need. Choose categories with accurate labels that match your methodology and analysis. Before you spend too much time designing the layout of your table, check that you are following the format expected within your discipline or organisation as table formatting requirements often vary considerably; if you are preparing a science report, refer to the relevant In-House Style Guide(s) or if you are preparing a journal article, meticulously follow the journal’s Instruction to Authors.

Title or Legend

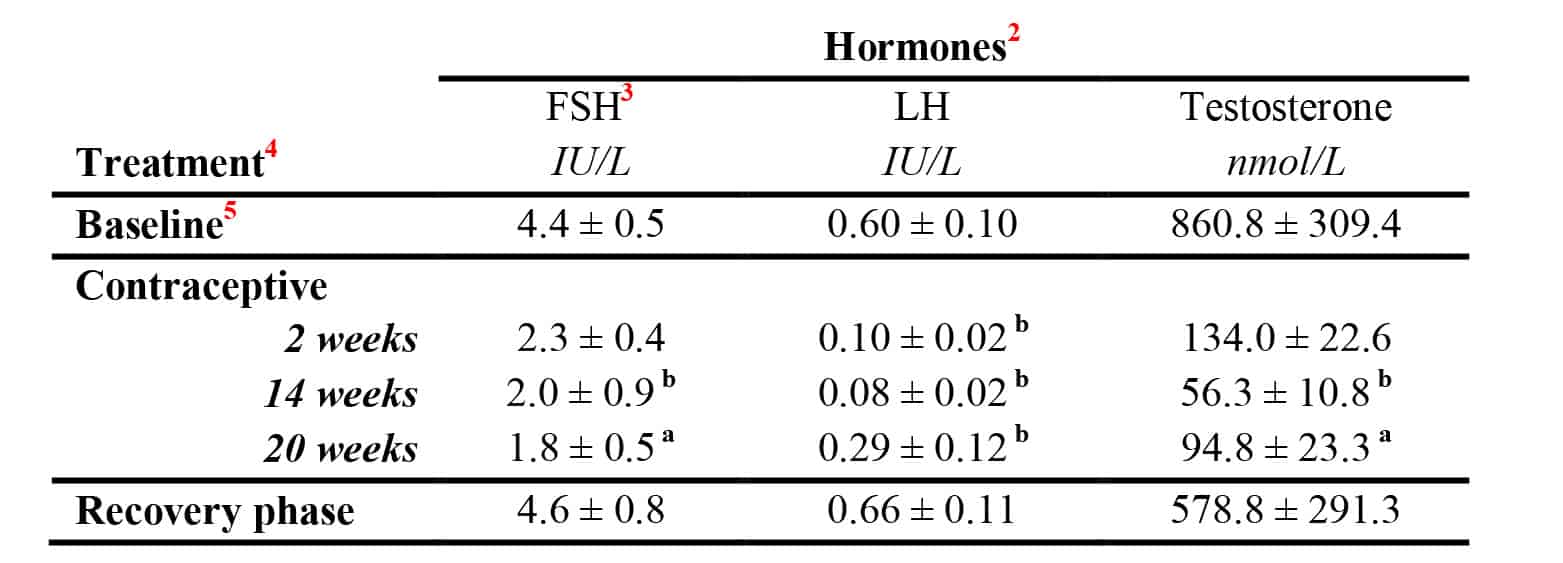

Consider the objective and key message of each table. The table title is typically placed at the top of the table. It should stand alone: it needs to be clearly understood by your target audience without them needing to go back to the results or methods sections. The title should be concise and describe what was measured, e.g. ‘Reproductive hormone levels during contraceptive administration in men’. Frame the title so that it conveys the key results, e.g. ‘Reproductive hormones are suppressed during contraceptive administration in men’.

Sub-headings

Take care to ensure the sub-headings are meaningful and accurate. The row and column headings clearly explain the treatment or data type, and include units. In the sample table below, the experimental details are given in the row headings (time points during the administration of a contraceptive), and the data measured (hormones) are given in the column headings.

Example Table

Explanatory notes

Explanatory notes and footnotes are placed at the end of the table. Make sure that all abbreviations are defined and that the values are explained. For example, if the values are a percentage, mean ± SEM, n per group.

Drawing and formatting the table

Tables for publication can be created in Word, using the 'Insert Table' function. For instructions see: Office Support: Insert or create a table.

- Tables can also be created from existing datasets in Excel, and then cut and pasted into Word, or exported into Word as an image.

- Use a separate cell for each piece of information; avoid having to insert tabs or spaces which may cause the text to be unintentionally moved when the formatting is adjusted.

- Add your headings and data to each cell. Cells can be merged to create headings above sub-headings. Select the cells you want to merge then select the 'Merge Cells' option.

- The table then needs to be formatted to improve readability and clarity. Select the entire table or individual rows or columns and right click. Options will appear where you can modify the table size, cell height and width, and format the borders. Word tables will have borders on each side of the cell by default.

- Format the borders by selecting columns, rows or individual cells will help the table to take shape and improve visual clarity. Text within the table can be formatted by selecting the text, then formatting it as normal.

- Make sure that the columns and rows are well separated and that the table is not cluttered and is easy to read. Imagine the reader looking at your table: do they have access to all of the information they need and can they easily understand the results?

Formatting borders helps a table to take shape and improve clarity. Select and de-select the horizontal and vertical lines you want to use as borders

Citing the table

Always cite the table at the relevant point in your text. Avoid repeating the details that are presented in the table, and use the text to direct the reader to the main message, e.g. ‘Contraceptive administration at 14 and 20 weeks significantly suppressed FSH, LH and testosterone levels in men (Table 1)’. Tables should be numbered consecutively throughout the document.

Further reading: (external links)

* Creating tables in scientific papers: basic formatting and titles

* How to create and customize tables in Microsoft Word

* Tips on effective use of tables and figures in research papers

* Tables and Figures

* Office Support: Insert or create a table

© Dr Liza O’Donnell & Dr Marina Hurley 2019 www.writingclearscience.com.au

Any suggestions or comments please email info@writingclearscience.com.au

Find out more about our new online course...

Now includes feedback on your writing Learn more...

SUBSCRIBE to the Writing Clear Science Newsletter

to keep informed about our latest blogs, webinars and writing courses.

FURTHER READING

- Co-authors should define their roles and responsibilities before they start writing

- The difference between a writing rule and a good idea

- When to cite and when not to

- How to create figures from data

- Back to basics: science knowledge is gained while information is produced

- How to build and maintain confidence as a writer

- If science was perfect, it wouldn’t be science

- The essentials of science writing: What is science writing?

- 8 steps to writing your first draft

- Two ways to be an inefficient writer

- Work-procrastination: important stuff that keeps us from writing