Why is it crucial to develop confidence?

If writing is central to your profession, it is crucial to build and maintain confidence in yourself as a writer. Being confident about your writing is being able to:

- rely on yourself to regularly produce high-quality material

- concentrate on creating and developing new ideas and solutions to new and existing problems, instead of worrying about whether your writing is good enough

- consider writing as a tool rather than a chore

- find writing enjoyable and rewarding

If you are committed to improving your writing, then your self-confidence will build as your writing improves. No matter how you feel about your current level of skill, commit to continual self-improvement and aim to feel satisfied with what you have achieved so far. This is what I do.

Realise that writing consists of separate tasks

Rather than considering writing as one discrete task, identify the different activities associated with writing and review how proficient you are at each one. Then work on improving each task separately. For example:

- Getting started

- Conceiving and developing ideas

- Word choice: Choosing the right words to say what you mean

- Phrase construction: Choosing the right group of words to say what you mean

- Clause and sentence construction: Expressing ideas concisely, logically and coherently

- Paragraph construction: Linking ideas in a logical order and developing a stand-alone story

- Developing an argument: Identifying different viewpoints and effectively stating your case

- Forming unique conclusions: Outlining your contribution to your discipline

Be kind to yourself

It is important to critique your writing and identify what can be improved, but avoid harshly criticising yourself.

(Everyone knows this but…) Be realistic about the time it takes to write

The time needed to complete a document is always underestimated. You need to allocate sufficient time to write regularly. Be realistic when working out how much time is needed to write. Make sure you plan your writing before you start. Avoid work procrastination.

Never compare yourself to others

Only compare your current level of skill to your past level of skill. Regularly look back at your past work and identify how your skills have improved. Observe how far your skills has progressed and allow yourself to feel satisfied with any improvement, no matter how small. Identify areas that need further improvement and allow yourself to gain confidence from your ability to identify what needs improving. An important part of skill development is getting better at recognising what needs improvement.

There are many ways to improve your writing

Identify the ways you can learn to improve your writing; for example, resources, books, blogs, writing workshops, online courses or one-on-one coaching assistance.

Get regular feedback

Always ask colleagues for feedback. Always. But make sure that you critique the feedback you receive, as not all of it may be useful or correct. Avoid taking any constructive criticism personally and avoid seeking feedback from those who regularly deliver overly-harsh criticism or tend to only give you praise.

Find a mentor or a colleague who can regularly give you constructive feedback. Join a writing group and share drafts with each other for peer-feedback and community support.

Blog

Set up a blog. Even if it is on a topic unrelated to science writing. Find a type of writing or topic that you really enjoy. Any type of writing will help improve your science writing skills, especially if you blog regularly.

Break through writer’s block

Use the tools that help break through writer’s block. Regularly having problems getting started may add to a lack of confidence. One quick and easy way of getting your thoughts down for a first draft is to record yourself speaking about your topic. Most smart phones and tablets have voice recognition software that can easily record or transcribe your speech.

Keep a portfolio (or library) of everything you complete

Keep a record of everything you produce. Create hard-copy portfolios of all your documents and include a table of contents with dates and titles. These portfolios can serve as a physical reminder of your productivity. Write one-page summaries of all completed projects in plain English with an eye-catching photo or diagram, and a good title. These one-page project summaries can be used to promote yourself and can also be prepared as a portfolio to show prospective employers.

Build confidence from your ability to learn

Remember that writing is like any other task with obstacles to overcome. Although it takes time for to become proficient at any skill, you can still be confident about your ability to learn.

Keep going

Keep writing, keep putting your work in front of an audience and keep getting feedback.

© Dr Marina Hurley 2018 www.writingclearscience.com.au

Find out more about our new online course...

Now includes feedback on your writing Learn more...

SUBSCRIBE to the Writing Clear Science Newsletter

to keep informed about our latest blogs, webinars and writing courses.

FURTHER READING

- How low-confidence can reduce the quality of your writing

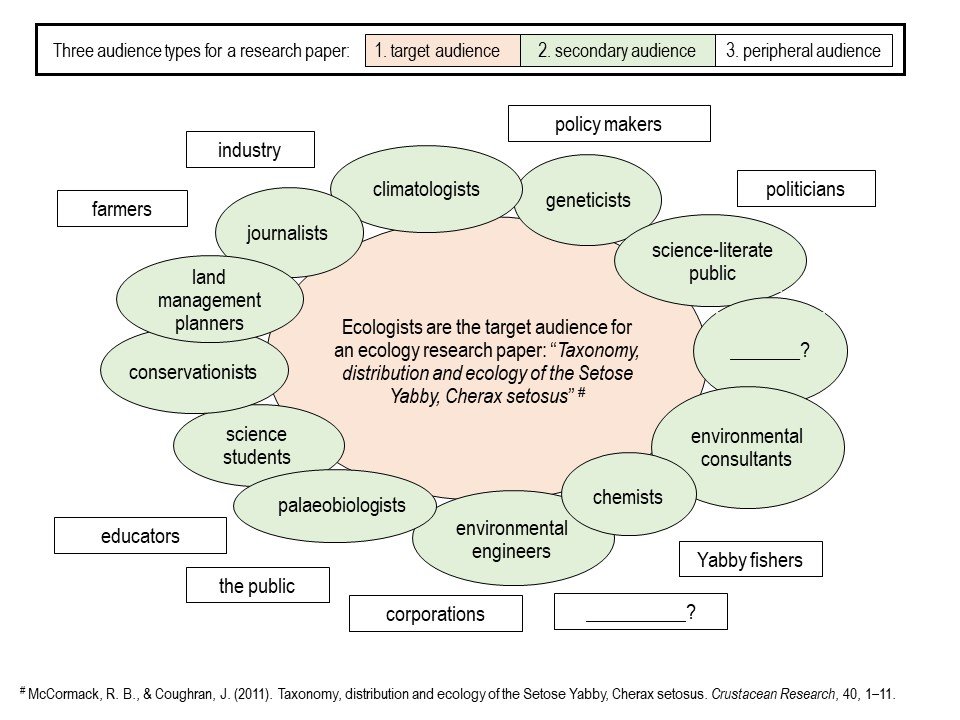

- The essentials of science writing: identify your target audience

- The essentials of science writing: plan before you write

- The essentials of science writing: What is science writing?

- 8 steps to writing your first draft

- Two ways to be an inefficient writer

- Work-procrastination: important stuff that keeps us from writing

Any suggestions or comments please email info@writingclearscience.com.au